(Previously published 12 April 2014. Kind thanks to Catcher in the Reel for permission to repost.)

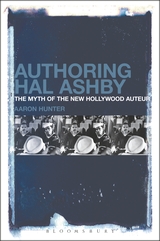

By Aaron Hunter

Under the Skin is a film that dares you to like it. Perhaps “like” is not the right word. “Enjoy” is closer to what I mean. Under the Skin is rather easy to like in the abstract – if one is a fan of art films, thoughtful (or, depending on your point of view, superficially thoughtful) films, non-mainstream films of any stripe, then it’s easy to think Under the Skin is a great film, a cool film, a provocative film. But to actually enjoy sitting through it is another thing – to thrill at experiencing its many repetitions, its long stretches with little or no action, its many confusing sequences. It’s one of those films that tells the viewer, I know you want to enjoy this, you probably think you’re supposed to enjoy this, but let’s see what watching it actually does for you!

The film, directed by Jonathan Glazer (Sexy Beast, Birth) and based on Michael Faber’s novel of the same name, stars Scarlett Johansson as an otherworldly being on a mysterious collection mission in Glasgow, Scotland. Whether she’s an alien or some sort of cybernetic being is not totally clear, but she does seem to work for aliens. And her mission? To collect the young men of Glasgow – mainly, it seems, working class men with few attachments to family or other people (likely to increase the length their absences will go unnoticed) – for nefarious purposes. In her capacity as collector, Johansson drives around the city in a nondescript white van asking for assistance from unsuspecting young men, whom she then ushers to “her place,” an isolated old pile that houses more than its exterior implies. Once inside the men are tricked into removing their clothes and then slipping into a sort of alien bath from which they’ll not return. Continue reading